Something to write home about:

In the Dock?

A place frequented by Merrill; perhaps too frequently during the mid-1930’s.

THE MASON CITY COURTHOUSE

Back to More Merrill Musings

A Soundtrack In My Head

The prologue of Where’s Merrill makes reference to the fact that I wrote large portions of the novel with a certain piece of music playing in my head. This was the rather unique instrumental titled Music For A Found Harmonium, and a link to the original and most fascinating rendition of this tune by The Penquin Café Orchestra is provided below. This piece of music was composed by the co-founder of the experimental orchestra, namely Simon Jeffes. Appropriately enough, the story behind the composition is that Simon found a harmonium whilst on tour in the Far East and sent it to a friend’s house in Kyoto. When he later visited his friend and his “found harmonium”, he was inspired to write an unforgettable yet simply structured composition which suited the quirkiness of the instrument.

In turn, Jeffes’ relentless harmonium tune inspired me to put into print the passages which…

View original post 1,935 more words

The Merrill & Sabrina Love Theme

Stranger In The House by Elvis Costello, here dueting with the wonderful George “No Show” Jones.

This never was one of the great romances

But I thought you’d always have those young girl’s eyes

But now they look in tired and bitter glances

At the ghost of a man who walks ’round in my disguise

I get the feeling that I don’t belong here

But there’s no welcome in the window anyway

And I look down for a number on my keychain

‘Cause it feels more like a hotel everydayThere’s a stranger in the house; nobody’s seen his face

But everybody says he’s taken my place

There’s a stranger in the house no one will ever see

But everybody says he looks like meAnd now you say you’ve got no expectations

But I know you also miss those carefree days

And for all…

View original post 556 more words

US Mormon ancestry records pre-date surviving Irish RC parish registers

It is strange to consider that the Mormon church, founded in the 1820′s, possesses original ancestry records which pre-date surviving Irish Catholic parish registers and make reference to Irish vital events in the 18th century – before the Mormon church even existed. How can this be? Well … it needs a series of very unusual historical happenings to have taken place in an Irish ancestor’s life, and one such ancestor was Johanna O’Connor born in County Kerry in 1807. Her amazing life story was summarized in a recent post on this blog. Refer to Irish Mormon Pioneer.

The key to being able to use exclusive Mormon records to identify ancient Irish family tree members whose names do not appear in preserved Irish church registers is that your research subject must have converted to Mormonism. Conversion from devout Roman Catholicism, as practiced in 19th century Ireland, to the new and very controversial Mormon religion which expanded from American roots to English towns in the 1840′s was literally a major “leap of faith” for any Irish man or woman. Very, very few would fit this ancestral profile. Johanna was not the only Irish person who settled in Utah over 150 years ago, but I have yet to come across another Irish Catholic ancestor who survived the harsh LDS pioneer trail and subsequently filed her mainly 18th century genealogy. Let me know if your own Irish family history contains a similar character.

In case you are unaware of Mormon doctrine, a practitioner of this religion is obliged to “baptise” (by proxy) any deceased non-Mormon relative into their Christian church. The deceased ancestor is then believed to have the right to accept or reject the baptism into the Church of the LDS, and Mormon followers consider that acceptance of the LDS faith ensures that the deceased can enter the Kingdom of God [Heaven]. This practice started in 1840, and towards the end of her life, Johanna spent many days during 1889 and 1890 baptizing over 50 members of her extended family. Until recently, we knew where Johanna’s marital in-laws came from (because they feature in corresponding Anglican church registers) but the precise roots of 35 listed Irish relatives could not be established, except that they all came from County Kerry according to Johanna’s LDS Temple notes. It was apparent to every researcher who studied the names that they did not exist in Irish record collections. So where were all these inter-related Irish folk from?

The LDS Registrar for Johanna’s baptisms by proxy left one clue by way of some semi-legible scrawl. Alongside the name of Johanna’s father, we could see a town birthplace written as “Bally B- – -”; the last three letters could be interpreted in several ways. The mystery was only solved when genealogists from Price & Associates contributed one extra clue left behind when Johanna passed away in 1894.

Here is my transcription of all the wonderful ancestral information which Johanna was able to recall:

1889 LDS Baptisms for the Dead (of Johanna O’Connor Farmer’s family)

In most ancestry projects, the goal of the genealogist is to discover the dates of the three normal vital events of their research subject, i.e. birth, marriage and death. The exact places where these events took place is also high on the research agenda. When a researcher is successful enough to track down the date and place of death of the ancestor in question, this information can be used to search for a published funeral notice or obituary … and an obit often opens up links to many “lost” family members who attended the funeral or were given respectful mentions as relatives of the deceased. In Johanna’s case, we thought that the discovery of a four sentence obituary in the Manti Messenger was the sum total of contemporaneous tributes to a remarkable Irish lady. Sadly, the local Manti newspaper article did not reveal anything about Johanna which we didn’t already know, after thorough research.

Therefore, it was with great surprise and delight when Diane Rogers from Price & Associates discovered that the Deseret News, the LDS Church’s oldest newspaper in Utah, printed a long tribute celebrating Johanna’s unique life after her demise in 1894. It was a joy to see that the obituary listed obscure facts about Johanna’s life which we had already unearthed from other research sources. Our complicated research processes were fully justified, but it was a bonus to read about other tidbits of Johanna’s life story and her character traits which, until now, we had only been able to speculate about. Finally, we knew for certain that Johanna was the pioneering woman we had envisioned and admired.

The Deseret News obit provided one new and crucial O’Connor birthplace clue. As shown below, it states that “Joanna Farmer, was born in Castle Island, County Kerry” [sic]. At last, we had a specific region of County Kerry to investigate. Castleisland is a small town and large civil parish in SW Ireland.

Some very intensive studies of the distribution of O’Connor families around Castleisland and the unique geography of the area eventually led me to “Ballybane”, the curious place which widowed Mrs Johanna Farmer referred to as her ancestral homestead in her 1889/90 LDS Temple notes.

There is no townland called Ballybane in the civil parish of Castleisland, although namesake places exist in other parts of County Kerry according to the national database of Irish place names. It appears that Johanna referred to her birthplace by its common local name which preceded the formalization of Irish townland designations. In my opinion Johanna was born in Ballybane which forms the southern portion of the townland of Ballyduff, located about 10 miles north of Castleisland town. This region falls within the RC parish of Knocknagoshel, but the local Catholic church registers only survive from December 1866 onwards. So Johanna’s detailed listing of her parents’ generation and her grandparents informs us about a complete Irish family that does not feature in record collections of Irish origin. By accident, Johanna has created a unique Irish Catholic family tree which pre-dates County Kerry parish registers by over 100 years.

There is no townland called Ballybane in the civil parish of Castleisland, although namesake places exist in other parts of County Kerry according to the national database of Irish place names. It appears that Johanna referred to her birthplace by its common local name which preceded the formalization of Irish townland designations. In my opinion Johanna was born in Ballybane which forms the southern portion of the townland of Ballyduff, located about 10 miles north of Castleisland town. This region falls within the RC parish of Knocknagoshel, but the local Catholic church registers only survive from December 1866 onwards. So Johanna’s detailed listing of her parents’ generation and her grandparents informs us about a complete Irish family that does not feature in record collections of Irish origin. By accident, Johanna has created a unique Irish Catholic family tree which pre-dates County Kerry parish registers by over 100 years.

More recent records indicate that many members of the O’Connor family still reside in and around Ballyduff townland. I would be pleased to converse with anybody who believes that they have connections with the ancient O’Connor and Kirby ancestors listed in Johanna’s Baptisms for the Dead.

After life’s fitful fever she sleeps well

A pioneering Irish Mormon

Owing to the non-preservation of the majority of 18th century Irish church parish records, and a fair few of the early 19th century registers, the branches of most Irish Family Trees cannot grow with much clarity beyond the years preceding the Great Famine. This is highly frustrating unless you come across rare circumstances in which an ancient Irish forefather wrote down their known ancestry in a formal manner for the benefit of all following and related descendants. This might have happened if your Irish ancestor was wealthy and/or descended from the British gentry. These types of ancestor could afford to employ academics to research and preserve their family history. Poorer folk, usually immigrants into the New World, occasionally created their own Family Bible from passed down oral histories in which the early family genealogy was listed haphazardly – but even this kind of valuable scribble (if found) in the front…

View original post 1,458 more words

Mini-Merrill

In our search for Merrill, we traced the lives of all his possible associates. This meant researching the whereabouts of all identifiable members of Merrill’s complicated extended family. In doing so, we came across one very eccentric character called Andrew Hessler who led a fascinating life with echoes of the Mystery of Merrill, although this man’s antics occurred a few decades earlier and culminated with his shocking death in 1915. As a result of my strange findings, I christened Andrew as Mini-Merrill.

If you‘ve read Where‘s Merrill, you will recall that Horace Forster’s mother was Amelia, and when her husband Leo Forster Jr shot his brains out after five years of marriage in 1886, we found out that Amelia eventually got married again to this fellow called Andrew Hessler – but this second husband “disappeared” (just like Merrill) during 1900 amid rumours of suicide.

I take some comfort regarding my…

View original post 873 more words

Where’s (Merrill) the Synopsis?

The basic story ….

“Where’s Merrill?” is a uniquely crafted mystery thriller based upon real life historical events. In fact, it is two inter-related stories in one novel set in different time-frames namely the past and the present. An Irish genealogist called Jed is commissioned by Tim, an American client, who needs to understand more about his mysterious maternal ancestry. Fate had dictated that Tim never got the chance to meet his grandparents, and he didn’t even know the name of his mother’s father. She refused to tell Tim, even on her death bed. Why? That was a question which troubled Tim as he witnessed his mother’s melancholy throughout his adult life, and after her death he resolved to find some answers – and peace of mind.

It was also a question which intrigued Jed after he learned that Tim’s grandfather simply “disappeared”. No death record, no burial – nothing. Jed identifies the “missing” grandfather…

View original post 144 more words

Another Irish emigration sailing disaster

I have previously recounted the sorry tale of the plight of dozens of poor Sligo natives who were attempting to escape famine conditions in 1848 by sailing to the Port of Liverpool for onward connections to other far-flung destinations. Half of the passengers never made it beyond Londonderry. Read more here: Sligo sailing disaster. Below is an account of another tragedy at sea, less than 12 months later, this time involving over a hundred souls fleeing from the north-west of County Clare and Connemara in County Galway.

On 7th September 1849, the St John, a brig of about 200 tons, sailed out of Galway harbour bound for Boston. She was owned by Henry Comerford of Galway and Ballykeale House, Kilfenora, and Captain Oliver from Bohermore in County Galway was in command. Aboard were nine crew members and about a hundred passengers in two main parties from Clare and Connemara, although later investigations asserted that the captain might have been illegally carrying another 30 emigres not entered on to the official manifest. On Saturday 6th October, the ship came close to land near Cape Cod almost at the end of her journey to Massachusetts Bay. The voyage had been a good one and so the captain issued a ration of grog to the crew in celebration. Captain Oliver suggested to the passengers that they too might celebrate their last night aboard the St John. The Irish human cargo had every reason for merriment; they had left far behind them a country of starvation, disease and death. The voyage had been less of a trial then they had expected and they were in sight of the shores of the Promised Land. They hurried to decorate the rigging and decks with candles and passed the night with traditional Irish songs and dance.

At five o’clock in the evening the brig passed Cape Cod Light and by one o’clock in the morning the First Mate guided the St John around Scituate Light. All of a sudden, the ship caught the wind of a fierce north-easterly gale and was soon being driven towards the shore. The rigging was hurriedly adjusted and a new, safer course was set. By daylight, the gale had become a full storm and the ship was being blown southwards along the Massachusetts coast. An hour later, on a mountainous sea, the St John was sighted at the mouth of Cohasset Bay. Inexorably the wind drove the little ship closer and closer towards the shore, with all hands on deck fighting to regain control of the St John over insurmountable elements. It was to no avail; the sails were now in shreds and the storm too powerful to fight. Both anchors were dropped but they dragged. As a last resort, Captain Oliver had both masts cut away but the wind and seas were relentless and the brig was helplessly forced onto Grampus Ledge. It was then about seven o’clock on Sunday morning.

Enormous waves lifted the stricken vessel and smashed her again and again on the rocks. The impact broke her back and opened her seams. A hole was quickly broken in her hull and those below decks were drowned within minutes. Pounded against the rocks, the brig began to break up. Horrified spectators saw people being “swept in their dozens” into the boiling surf from the crowded decks. Even though they were deafened by the howling of the wind and the thunder of the seas, the watchers were convinced that they could hear the screams of the unfortunates as they were dragged to their deaths. Sickeningly, there was nothing any bystander could do to help.

The jolly boat (or tender) had been hanging by its tackle alongside the brig. Suddenly, the stern rigging bolt broke and the small jolly boat fell into the water, in danger of being swept away. The captain, the second mate, two of the crewmen and two apprentice boys jumped into the maelstrom and managed to secure her, but immediately about twenty-five frenzied passengers attempted to board the little boat and it was swamped. Of the people in or around the jolly boat, only one survived – Captain Oliver, who managed to grab a rope which was hanging from the main deck and was pulled aboard the ship by the first mate, Henry Comerford (believed to be a nephew of the ship’s owner of the same name).

The jolly boat (or tender) had been hanging by its tackle alongside the brig. Suddenly, the stern rigging bolt broke and the small jolly boat fell into the water, in danger of being swept away. The captain, the second mate, two of the crewmen and two apprentice boys jumped into the maelstrom and managed to secure her, but immediately about twenty-five frenzied passengers attempted to board the little boat and it was swamped. Of the people in or around the jolly boat, only one survived – Captain Oliver, who managed to grab a rope which was hanging from the main deck and was pulled aboard the ship by the first mate, Henry Comerford (believed to be a nephew of the ship’s owner of the same name).

Another group of passengers jumped into the water in an attempt to reach the overturned jolly boat, but they all perished in the cruel sea. By now the main ship was rapidly disintegrating. The water around her was strewn with wreckage to which people clung desperately even though they were again and again buried beneath tons of water as the colossal waves broke over them. The captain, the first mate and the remaining seven members of the crew eventually succeeded in re-securing the jolly boat using grappling hooks and all safely swam to and (shamefully) boarded the makeshift lifeboat and headed off to shore; only one stranded passenger was collected en route.

By eight a.m. the ship had completely broken up and the worst horror was over. In total, eight women and four men had made their own way to the shore, semi-conscious through exhaustion. Two passed away on the beach and the remainder had to have their hands prised from the wreckage which had saved their lives. News of the disaster spread along the American coastline and by early afternoon the shore was lined with people who worked unsparingly to resuscitate the living and retrieve the dead. The survivors had many stories to tell. Two of the women who had fought their way ashore had each lost three children. The human loss was horrendous. A man called Patrick Sweeney of Galway perished with his wife and nine children. Many of the recovered bodies were badly mutilated by the jagged rocks, yet Sally Sweeney’s features were reportedly “calm and placid as if she were enjoying a quiet and pleasant slumber.” There was one tiny miracle: Mr Lathrop, in whose house the survivors found shelter, waded into the surf to retrieve a parcel of clothing and discovered that he had an infant in his arms. Some days later the baby was said to be in excellent health.

A newspaper report of the time says that forty-six bodies had been taken from the sea by nightfall, and that they were coffined in rough deal wood boxes on the beach. The storm raged on at sea for two more days as religious ceremonies on the shore and in the local cemetery took place. Immigrant family relatives rushed from waiting rooms at Boston Harbor to the scene upon hearing news of the disaster. Irish women howled each time a loved one was recognized in the lines of wooden boxes. Many unclaimed victims were buried in a common grave on Tuesday. The funeral party was headed by the captain and the survivors.

A newspaper report of the time says that forty-six bodies had been taken from the sea by nightfall, and that they were coffined in rough deal wood boxes on the beach. The storm raged on at sea for two more days as religious ceremonies on the shore and in the local cemetery took place. Immigrant family relatives rushed from waiting rooms at Boston Harbor to the scene upon hearing news of the disaster. Irish women howled each time a loved one was recognized in the lines of wooden boxes. Many unclaimed victims were buried in a common grave on Tuesday. The funeral party was headed by the captain and the survivors.

Sixty-five years later a huge granite Celtic Cross was raised over the mass grave, sited on the highest point of Cohasset Central Cemetery so as to command a view of the bay. The cross bears the inscription: “This cross was erected and dedicated May 30, 1914, by the A.O.H. and the I.A.A.O.H. of Massachusetts to mark the final resting place of about forty-five Irish immigrants from a total company of ninety-nine who lost their lives on Grampus Ledge off Cohasset October 7, 1849, in the wreck of the brig St John from Galway, Ireland. R.I.P.“

If you can stomach an even more harrowing version of events, here’s a link to newspaper reports of the time: 1849 St John disaster

Fascinating Firewood

For over eighteens only ….

The Carling Brewery has introduced an odd marketing campaign in the west of Ireland. If you purchase sufficient cans of Black Label lager beer, the purchaser is given a box of J-Blocs – with no explanation as to why the purchaser deserves such a bizarre gift. The J-Blocs box indicates that only persons over 18 years of age are entitled to this gift. Fair enough. You have to be 18 to buy beer in Ireland. Another teaser states that you need “steady hands” to handle the mysterious J-Blocs box.

I opened the box when I got home from town. It was full of neatly cut sticks of firewood. With steady hands, I lit a fire in the hearth. The J-Blocs added to the glow of burning sods of turf in no time at all. It’s a clever idea. Stay in, booze at home and keep warm.

A pioneering Irish Mormon

Owing to the non-preservation of the majority of 18th century Irish church parish records, and a fair few of the early 19th century registers, the branches of most Irish Family Trees cannot grow with much clarity beyond the years preceding the Great Famine. This is highly frustrating unless you come across rare circumstances in which an ancient Irish forefather wrote down their known ancestry in a formal manner for the benefit of all following and related descendants. This might have happened if your Irish ancestor was wealthy and/or descended from the British gentry. These types of ancestor could afford to employ academics to research and preserve their family history. Poorer folk, usually immigrants into the New World, occasionally created their own Family Bible from passed down oral histories in which the early family genealogy was listed haphazardly – but even this kind of valuable scribble (if found) in the front or back of a family heirloom book can sometimes be proved to be less than 100% reliable. Long-believed family lore is not necessarily family fact.

So – could there be any way of discovering the names of the parents and grandparents of an Irish native born into virtual poverty at the beginning of the 19th century, and from a rural region where no parish registers survive until about 1850 onward? Well, yes – if you are very lucky. I came across an Irish ancestor who lived a fairly unique life, and detailed research into her background eventually led to the unearthing of parental information plus the full names of the four grandparents born in a remote part of Ireland in the mid-1700’s.

This ancestor was Johanna O’Connor born on 20th December 1807 in County Kerry, SW Ireland, in the parish of Castleisland. Many of her poverty-stricken peers headed west to America and Canada in order to escape annual hardship and near-starvation as part of large Catholic families living in mud and timber shacks, eking out an existence on barren mountainside farm fields leased to them by absent, greedy landlords. In most cases, the ancestral farmland had been stolen from the Kerry natives by invading English armies centuries ago, and then distributed among the army’s officers and financial backers. The local families then had to pay extortionate rent for the privilege of remaining in their primitive homes located on land which their ancestors had farmed as far back as medieval times. Johanna’s story of survival took an unusual route though.

For reasons unknown, some of Johanna’s older relatives had migrated in the opposite direction to the beckoning Atlantic Ocean. We now know that some of her extended family members were living in London, England, by the 1830’s. As a young lady, Johanna must have been invited to London to escape the West of Ireland poverty trap. It would have been a mind-boggling cultural shock for the girl from a windswept Kerry mountainside to find herself in the biggest city in the world, at that time, complete with its busy and dirty streets lined by overcrowded tenement housing blocks.

In 1835, at the age of 27, Johanna became acquainted with a moderately successful Englishman named John Smith Farmer. Her subsequent fiance came from a completely different background. John was the son of a comparatively wealthy merchant from Wolverhampton in the English midlands, and after joining the family business he too found himself in London as the purchasing agent for goods sold in the Farmer stores. The romance seemed more unlikely because John was from an established and respected Anglican family whereas Johanna knew of no other faith than Roman Catholicism. Nevertheless, their courtship led to a marriage in London, and Johanna had no qualms about converting to the Protestant church to appease her in-laws.

John & Johanna set up a marital home in the Wolverhampton Black Country where John’s mother still resided. There, in the space of seven years, Johanna conceived and delivered two daughters followed by a son. In the early 1840’s, John & Johanna became fascinated by the new religion of Mormonism and invited visiting Elder Lorenzo Snow to preach in their Wolverhampton home. Then a double tragedy struck the Farmer family – John’s mother passed away, and not long after in January 1844, John Smith Farmer himself died after developing a painful bowel complaint. He was only aged 35 years at death.

Johanna was now widowed and living in an unfamiliar English city, trying to raise three young children. Those of her in-laws who were still alive could not afford to support extra family members, as the Farmer Factor businesses fell into decline. Johanna quickly dropped in status from middle class housewife to impoverished beggar woman, wondering why the Good Lord had allowed her dreams to be shattered. She turned to the supportive Mormons to find an answer.

Mormonism, developed in America during the 1820’s, arrived in England via missionaries in 1837. The new Christian doctrine spread southwards from its first base in Preston, Lancashire, allowing local Elders to establish branches in most of the industrial cities and towns of northern England. In these places, the missionaries were able to convince desperate down-and-outs or persecuted manual workers that a better life awaited them in new Mormon settlements in the Wild West of America. More significantly, the officers of the burgeoning Mormon Meeting Houses were able to offer a radical credit system to permit destitute would-be emigres to board ships from the Port of Liverpool bound for America on the understanding that their passage must be repaid from wages earned in the Mormon camps. Thousands of English and Welsh families signed up and made the treacherous journey west, over rough seas, and even rougher pioneer trails. Among the pioneer immigrants were a few Irish, Scottish and Scandinavian natives, caught up in the migration for a variety of reasons. Irish widow Johanna with her English children fell into the latter category because of her previous conversion to Protestantism and residency in England for a decade. Six weeks after her husband’s death, Johanna took the plunge and sailed across the Atlantic with her young family.

The promise of a new life in the New World, and an escape from the threat of the feared Workhouse institutions, clearly had its appeal to a woman not yet aged 40; a woman who had escaped poverty in her Irish homeland as a youngster. Johanna arrived in the newly-established Mormon city of Nauvoo, Illinois, just in time to see the Mormon founder Joseph Smith arrested for polygamy. Later in 1844, Joseph Smith was murdered by an anti-Mormon mob who stormed the nearby Carthage jailhouse. Johanna and her children were forced to flee to the city of St Louis, an American Mormon stronghold. Here she stayed for ten years as her children completed their education. Her elder daughter found a husband, and her other daughter became a teacher – but Johanna’s journey to Mormon salvation was not quite complete.

By 1847, Brigham Young, the new leader of the Mormon Latter Day Saints, had sent his scouting parties out west to explore uncharted American territories. The Mormon dream was to colonize and develop a far western state in which all its church followers could resettle and prosper. Utah, and in particular the Salt Lake Valley, was to become the Promised Land. And so, in 1856, Johanna O’Connor and her teen-aged son loaded a few belongings into their ox-cart and joined one of many Pioneer Wagon-trains heading west to Utah. They had to travel through hostile native Indian territory and endure the extremes of natural weather conditions. Numerous pioneers perished along the way, and never saw Salt Lake – but Johanna survived again and settled in completely new and basic surroundings in the town of Manti UT.

Even though her son Joseph gave up the arduous Mormon lifestyle and religion, and soon returned to St Louis, Johanna appeared to thrive in the rural wilderness of Manti. Her new home must have had some similarities with the ruggedness of her County Kerry birthplace. Johanna lived for 38 years in Manti until her death in 1894, shortly before her 87th birthday. Her son Joseph returned to be with Johanna in her final days.

About five years before her death, Johanna followed the doctrine of Mormon founder Joseph Smith’s preachings and started to “baptize” her deceased relatives into the Church of the Latter Day Saints. In so doing, Johanna formally registered the existence of, and her relationship to, every family member she could recall who had passed away. Johanna managed to fill up three entire pages of the Mormon Baptismal Registers for the Dead over a 12 month period. The full names of each relative, and their origins, were meticulously recorded. Johanna baptized her parents, and grandparents, and uncles and aunts, and great-uncles and great-aunts, and siblings, and one deceased child. Then she moved on to step-relations because a grandfather had re-married after being widowed. Finally, Johanna listed and prayed for all deceased members of her English in-law family. Her memory in old age, far from her Irish homestead, was astounding. Further research indicates that Johanna regularly communicated by mail with family connections in England and Ireland because she had “up-to-date” knowledge of deaths which occurred long after her arrival in America.

The image below displays the first tranche of Johanna’s Baptisms for her dead relatives. The message for all Family Historians is simple. Never give up, and never rule out the outrageously unexpected. When I first started researching Johanna, I presumed that she was just your typical Roman Catholic Irishwoman who managed to escape the Great Famine and rebuild a life in the USA. How wrong can you be?

The Evidence?

“Where’s Merrill?” hits the Top Twenty

A sincere big thank-you to all readers and reviewers of my genealogical thriller “Where’s Merrill?” which today made it to the Top Twenty section of Amazon’s bestselling ebook Historical Thrillers.

That’s my kind of thrill.

Update: 27th Sep 2013

Also in Top 100 of all book types, Historical Thrillers.

I can’t see WM dislodging Stephen King’s latest offering from #1 though!

The Poteen Wars

Retrieved evidence verifies that the wild residents of the Ox Mountains in County Sligo, and in particular the Catholic parishioners of Kilmacteigue living by the Windy Gap overlooking Lough Talt, were highly-regarded distillers of some of the finest Mountain Dew ever sipped in Ireland. Highly-regarded, that is, by fellow aficionados of the home-brewed spirit known as Poteen. The British authorities and later the Civic Guard of the Irish Free State took a different view to the producers and imbibers of duty-free liquor.

As a result, an ongoing clandestine war was fought around the south Sligo mountains and boglands for centuries. The policing agencies always boasted of victories in isolated skirmishes, but truth be told, the distillers were never beaten. The “illegal” trading of mysterious lethal brews still persists to this day – albeit that the receptacles containing the wondrous concoction are more likely to be discarded white lemonade bottles these days (if the plastic does not melt).

The newspaper articles below give a “taster” of the never-ending Poteen War:

“ANOTHER ONE” led to the Civic Guards retreating to their Barracks in Aclare. The Poteen Pushers could not be stopped. Casual visitors to Cloongoonagh carried on their everyday business. Christmas was coming. Everybody was happy – even the Guards and the Judge, sampling the finest Mountain Dew prior to enjoying their fattened goose dinners.

If you want to know how to make Mad Man’s Soup follow this link at your peril:

Marasmus …. in Ireland

During a recent research project, I was shocked to come across an Irish death certificate for a baby girl named Martha aged just under 15 months upon which the Certified Cause of Death was declared by a physician to be “Marasmus.” This is the condition which often claims the lives of very under-nourished infants living in areas of severe famine. We have all seen the haunting images of terrified black children with bloated tummies and heads attached to skeletal frames filmed during recent famines in war-torn African countries. The medical term for the distorted human condition you were witnessing is marasmus.

However, my Irish death cert of concern was not from the Great Famine era of Ireland, namely the late 1840’s. Civil death registration in Ireland did not commence until 1864. This particular death certificate, shown below, dated from 1877 when Ireland had overcome the worst of the economic depression in the post-Famine years. So how could a one year-old baby just starve to death in a West of Ireland family home at this time? This was a scenario which troubled me, especially when my research revealed that baby Martha had six older siblings who all appeared to survive childhood with relative and commendable ease.

The death of Martha occurred on 28th February 1877 in the County Galway village of Kilchreest. The baby’s parents were Patrick & Margaret. On first viewing the certificate I noted that Margaret reported the death, and this was a common but tragic duty for the mothers of infants who died very young, but usually as a result of fever or generally sub-standard living conditions. MARASMUS though! This diagnosis bothered me.

It was not until my client commissioned me to investigate more fully the background of her Irish ancestors that I discovered the whole sorry tale of poor Martha’s last few weeks on earth. The story was more tragic than I could have imagined.

In being asked to compile complete Family Trees, it was one of my tasks to find out when Martha’s parents died. All of her surviving older siblings emigrated to America, but Martha’s parents never crossed the Atlantic Ocean to join them, and they were also absent from the 1901 Irish census. Logically, both of Martha’s parents must have died before April 1901 and after youngest child Martha’s conception in 1875. I eventually found a matching death record for Martha’s father, Patrick; he died in the year 1900 as a widower. For days after, I struggled to locate any reference at all to the demise of Martha’s mother, Margaret. She was dead by 1900, and she reported baby Martha’s death in February 1877, yet there was no matching death record in the intervening years in County Galway, or the whole of Ireland, or anywhere in the civilized world for that matter. I was stumped – until I made an accidental discovery.

For some reason I cannot recall, I carried out my search for Margaret’s death record one more time. On this occasion, I must have left the span of years for my database search engine to interrogate as Martha’s DOB (in 1875) up until 1900. Up popped mother Margaret’s death registration …. in November 1876 …. so mother Margaret had died three months before her baby Martha. Ugh? So who was the female with the same name as Martha’s mother who registered the baby’s death. It took a while before the truth dawned on me.

Earlier research had determined that Martha’s father, Patrick, was most likely an illegitimate child. Patrick could not name his father when he married Margaret, in spite of the fact that this was a normal legal obligation prior to a marriage being recognized by the British state. So Patrick had no family network to step in when his wife tragically died and left him with seven children to raise single-handedly. Patrick worked on a country estate looking after the land and domestic animals on behalf of wealthy employers, and I reckon that he felt forced to carry on with his work in order to keep his family fed, after Feb 1877. Then it HIT me! Patrick’s eldest daughter was Margaret, born in 1864. This girl was aged just 12 years when her mother died …. and 12 year-old Margaret then became the surrogate mother for her six tiny siblings. Somehow, she managed to keep them all alive as her father Patrick spent long hours away from the family’s cottage in Kilchreest village …. but baby Martha needed a proper biological mother.

12 year-old Margaret toiled as best she could, but eventually Martha could not retain nourishment. After three months in Margaret’s care, baby Martha gave up the will to live as an underfed deformed human soul, in front of Margaret’s eyes, and probably in front of a traumatized group of young siblings. Martha’s death certificate confirms that “Margaret” was “Present at Death.”

Having absorbed these facts, it then became apparent that little Margaret suffered the final indignity of having to formally report the death of her baby sister to the local Registrar. Technically, Margaret was under the legal age to carry out such a sad task – and where was her father Patrick when this matter was reported on 14th March 1877? In fact, where was any neighbourhood support in these days before Social Workers stepped in to ease the burden on dysfunctional families? Shame on them all.

Perhaps the worst castigation should be spared for the family’s local physician. This man calmly advised the Registrar that poor Martha’s condition of Marasmus had been certified for eight weeks prior to death! In other words, this so-called doctor was aware of Martha’s drastic under-nourishment by early January 1877 at the latest, yet he left a dying baby in the care of her 12 year-old sister …. and just walked away from the evolving tragedy.

The only good news is that Martha’s siblings all escaped the Irish poverty trap and all eventually settled in various parts of America. Amazingly, one of Martha’s sisters lived to the grand old age of 103 years and retained a computer-like memory right up until her dying day. When this day came in 1972, she could still recount the story of her baby sister who died back in the Galway cottage homestead …. where no-one seemed to care about fatal circumstances which scarred young minds forever.

1923: Aclare at War

Merrill the Hedgehog

For about the last two weeks, we’ve been feeding a hedgehog which was spotted in our front garden late one night. We understood that these creatures were very secretive and rarely ventured far from their nests – but we noticed that our visitor started to regularly take his feed of meat and biscuits by our illuminated front door every night at about 11 pm. By placing his food nearer to one of our outdoor security cameras, we also started watching him arrive and depart (after about 15 minutes of munching) in glorious infra-red night vision. Our hedgehog was a large adult and we christened him Merrill.

We were shocked on Saturday morning though, when we saw how huge our Merrill actually was in daylight. For reasons unknown, this normally nocturnal dweller, had decided to take a stroll around our garden in broad daylight. He was larger than a typical domestic cat.

Merrill proceeded to take a five minute jog around a circuit of our house. Hedgehogs can move at a surprisingly high pace, especially big fellows like mega-Merrill. He eventually ambled into our old stone barn and had a rummage through my stocks of winter wood fuel. Merrill sensed that I had spotted him and hid behind a thin branch of fallen timber. It wasn’t the best of hiding places.

Merrill is obviously grateful for his free dinners in the run-up to hibernation time and has become remarkably tame. He is not spooked by bright lights at night, nor by humans observing him at close quarters. Stray cats have approached him but his natural spiky defense system in combination with his vast size means that would-be predators soon lose interest in our Merrill. Only when he’s ready, with a full belly, does he trot off towards the garden fence and into a natural hollow protected by shrubbery.

I managed to capture the photo above, by chance, when Merrill scrambled up to the top of my wood pile and then lost his footing. He rolled backwards doing gentle somersaults, and had a soft landing in the hay. Feeling rather embarrassed he then went home for the day, and no doubt had a long sleep. At long last, I found Merrill – but I’ve promised to keep his address and whereabouts secret.

Interview

Published 2013-08-30 by Smashwords.

Aclare Old Fair Day (Revived) 3rd Aug 2013

Earlier posts recall the days when Aclare village in County Sligo hosted one of the busiest Fair Days in the region. Back in the 19th century and early decades of the 20th century, the main focus of attention for buyers and sellers alike was the trade in farming livestock, followed by boisterous quaffing of ale and whiskey in the village’s many old public houses.

Today, prompted by the more genteel and nostalgic mood of The Gathering of 2013, Aclare has stepped back in time and the dozens of long-deserted old shops and business premises have risen from the grave for one weekend only. There are not many beasts of the field around (for which the Tidy Towns’ appointed street-cleaner is eternally grateful), but market stalls are displaying farming antiquities alongside freshly baked breads and cakes, lovingly made in the old farmhouse kitchens of the surrounding countryside. With an old-style Dinner Dance (for the traditionalists) and a Disco (for the younger brigade) to follow, boisterousness in the pubs might yet make a comeback.

Thankfully, a growing tourism trade in our secret part of South Sligo is boosting the local economy, year on year. The unspoiled mountains and lakes appeal to young and old alike. More information about the area can be found via the link to our Walking Festival brochure (below). Everyone will be made more than welcome. Don’t all come at once though …. the beauty is in the serenity …. followed by great music and craic in the bars.

10 Questions

Try the WM? quiz:

Go on – it’s only a bit of fun.

If you’ve read “Where’s Merrill?“, then let’s see if you were paying attention.

If not, just guess – but at least one of the answers is on this blog.

1926 Drimina National School

As many schoolchildren prepare to start their long summer holidays at this time of year, no doubt collected from the school gates in their parents’ large 4-wheel drive vehicles and comfortable people carriers, few could possibly envisage what school life was like for their great-grandparents and even older ancestors. The following photo from the 1920’s taken outside the school my father attended in the west of Ireland provides a few insights. It is the earliest group photo I have come across from my ancestral heartland which portrays “ordinary” people, as opposed to local dignitaries dressed in all their finery.

First off, you will note that the boys were segregated from the girls. The Roman Catholic church governed the vast majority of rural schools in Ireland for decades until quite recently, and the parish ministers must have feared that seating growing lads alongside delicate lasses would engender temptations which were forbidden until much later in life (and only after marriage, of course). The older boys in the photo would have been in the senior school year and aged 13 or 14. Shortly after this end of term snapshot was taken, these senior boys would have been thrust into the big, wide world to fend for a living. For most, this would have simply meant working on their father’s farms until approaching age 20 when mammy might permit her son to board a boat, and sail off to a faraway country, possibly never ever to return. Dad could have had a more pragmatic view. His small farming income could not sustain the feeding of too many hungry adult mouths. It was better that the grown-up kids left home at the first opportunity, so long as they sent some cash gifts “home” to Ireland in the years before finding their own marriage partners.

Besides, the next oldest progeny would be ready to leave school, permanently, and take over the agricultural labouring duties of the departing emigre.

The next thing you will notice from the photo is that this snap was taken long before the introduction of school uniform clothing. In fact, it is almost a miracle that all the boys could turn up for the professional photographer’s end of term visit dressed in their (ragged) Sunday best jackets and trousers, some proudly displaying waistcoats like the country gentlemen they aspired to be. In reality, most of the clothing on show would have been well-worn by older brothers, and maybe even older generation members of the extended families of the Drimina National School pupils. Hand-me-downs were gratefully accepted. Tell that to the fashion-wary schoolkids of today who must boast the latest expensive designer labels – or “die of shame.”

But … the real shocker for today’s sports shoe-wearing youngsters is the clearly-visible evidence that many of their contemporaries from about 80 years ago had no footwear whatsoever during their schooldays. A decade after this photo was taken, my own father was walking bare-footed to this school from his remote hamlet a few miles away. So were all his school-friends. Of course, they protected their toughened feet by taking short cuts across fields and bogland, traversing streams as they went. However, the photo shows that the rough stone “playground” at Drimina must have caused sore heels and soles, especially when a very physical game of Gaelic football was organized by the young lads during intervals in between strictly-disciplined lessons.

1848 Sligo emigration sailing disaster

| NOTE – there is a certain graphic nature to this report of a tragedy at sea, as reproduced from a contemporary Irish newspaper. Some people may find it distressing. Please be warned.

DREADFUL OCCURRENCE ON BOARD AN IRISH STEAMER. A dreadful loss of life happened on board the steamer Londonderry, on her voyage from Sligo to Liverpool, last Saturday, (December 2). The stories given by the Irish papers were at first absurdly discrepant, both as to the cause and the extent of the calamity. The following account from the Belfast News Letter, appears most truthful:- The steamer Londonderry, Captain Johnston, one of the vessels belonging to the North-west of Ireland Steam-packet Company, and at present plying between Sligo and Liverpool, left Sligo at four o’clock on Friday evening for the latter port, with a general cargo, a large number of cattle and sheep, about 190 steerage passengers, emigrants on their way via Liverpool to America, and two or three cabin passengers. As she proceeded on her voyage the weather became exceedingly foul, and after midnight the wind rose to a perfect gale. About one o’clock that night, or rather Saturday morning, it was deemed expedient to put the steerage passengers below and the order was executed, not, we understand, without some resistance on the part of many of them. Most of our readers are probably acquainted with the dimensions of a steerage cabin of an ordinary steamer – a compartment rarely more than eighteen feet long by ten or twelve in width, and in height about seven feet. Into this space, ventilated only by one opening—the companion—150 human beings, as we have been informed, were packed together. We can only guess at the necessity which gave occasion for this apparently inhuman, and, alas fatal order; but it is reasonable to suppose that there was an apprehension lest some of the unfortunate passengers might have been washed overboard had they remained on deck, as the sea was at the time breaking over the vessel. The steerage being thus occupied, it was next, as alleged, feared lest the water should get admission through the companion : and this, the only vent by which air could be admitted to the sufferers below, was closed, and a tarpaulin nailed over it, thus hermetically sealing the aperture, and preventing the possibility of any renewal of the exhausted atmosphere. The steamer went on her way, gallantly braving the winds and waves, unconscious of the awful work which death was meanwhile doing within her. In the darkness and heat and loathsomeness of their airless prison, its wretched inmates shrieked for aid ! and there were none to hear their cries amid the boisterousness of the storm, or if they were heard, none sagacious enough to interpret the dreadful meaning they meant to convey. At length one man, the last, it is said, who had been put down, contrived to effect an opening through the tarpaulin of the companion, and pushing himself out, communicated to the mate that the people in the steerage were dying for want of air. The mate instantly became alarmed, and obtaining a lantern, went down to render assistance. Such, however, was the foul state of the air in the cabin, that the light was immediately extinguished. A second was obtained, and it too was extinguished. At length the tarpaulin was completely removed and a free access of air admitted. When the crew went below, they were appalled by the discovery that the floor was covered with dead bodies to the depth of some feet. Men, women, and children were huddled together, blackened with suffocation, distorted by convulsion, bruised and bleeding from the desperate struggle for existence which preceded the moment when exhausted nature resigned the strife. After some time the living were separated from the dead; and it was then found that the latter amounted to nearly one half of the entire number. Seventy-two dead bodies of men, women, and children, lay piled indiscriminately over each other, four deep, all presenting the ghastly appearance of persons who had died in the agonies of suffocation; very many of them were covered with the blood which had gushed from the mouth and nose, or had flowed from the wounds inflicted by the nail studded brogues, and by the frantic violence of those who struggled for escape. It was evident in the struggle the poor creatures had torn the clothes from off each other’s backs, and even the flesh from each other’s limbs. Nearly all the steerage passengers were poor farmers from the neighbourhood of Sligo and Ballina, with their families; and many of the dead were nearly naked, from poverty. The Londonderry put into Lough Foyle at ten o’clock on Saturday night, but for some reason with which we are not yet acquainted, she did not come up to the quay of Derry until ten o’clock on the following (Sunday) morning. The authorities hastened to the spot, and gave orders for the arrest of the captain and all his crew, and they were accordingly removed to prison under a military escort. An inquest was held on one of the bodies on Monday; and the Jury returned the following verdict— “We find that death was caused by suffocation, in consequence of the gross negligence and total want of the usual and necessary caution on the part of the captain, Alexander Johnston, Richard Hughes, first mate, and Ninian Crawford, second mate; and we therefore find them guilty of manslaughter and we further consider it our duty to express in the strongest terms our abhorrence of the inhuman conduct of the remainder of the seamen on board on the melancholy occasion; and the Jury beg to call the attention of proprietors of steam boats to the urgent necessity of introducing some more effectual mode of ventilation in the steerage, and also of affording better accommodation to the poorer class of passengers.” |

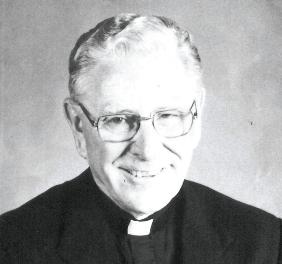

The Holy Lamb

I have previously referred to a Black Sheep in the family, in the form of an abusive priest of the worst kind. I am pleased to be able to introduce the antithesis of the abuser, the holiest man in my Family Tree, none other than Father Matthew O’Rourke, my first cousin once removed.

Matthew was born on 7th November 1918 in the Bronx district of New York City. He was the middle child of five O’Rourke siblings born to one of my grandfather Ned Neary’s sisters (Margaret) who had emigrated from the Sligo farmstead to New York in 1905. In the Bronx, Margaret married her brother-in-law, John O’Rourke, a Leitrim native and a fully-qualified and respected Civil Engineer who worked on many important NY infrastructure projects.

Margaret Neary’s first child, a daughter called Mary, died before the age of two when Margaret was six months pregnant with her second child. The new baby would have started to console John & Maggie O’Rourke over their sad loss, as this child was also a daughter, honourably christened as Margaret Mary in September 1916. The new baby developed into a strong, bright and independent young lady. By 1938, Margaret Mary had breezed through college studies and went in search of a career having been awarded a Major in the field of Chemistry. In 1940, Margaret Mary would have witnessed her younger brother Matthew leaving college with his own BA degree and then attending St Joseph’s Seminary to study to enter the priesthood. Matthew’s life choices must have influenced his older sister because in 1949 Margaret Mary gave up her well-paid employment and became a nun in the Order of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament. In fact, Margaret Mary lived her own long and holy life as she too devoted herself to God, becoming a Catholic teacher of native Najavo Indians in Arizona before eventually retiring to her convent in Pennsylvania. Margaret Mary died on 7th November 2008 in the convent hospital, aged 92, an event which upset Fr Matthew … for he was still going strong, and it was his birthday and he related the news of Margaret Mary’s death to me with much sadness in his voice.

During his seminary studies, Matthew was sent in 1944 to work in the poorest black communities of the Southern US states. He spent about a year in these communities, and what he saw was to inspire the majority of his adult life. Matt was fully ordained as a Josephite priest on 10th June 1947 after completing his ecumenical studies in Washington DC. He was awarded his first ministry as an associate pastor in a mixed race city center parish of New Orleans, and here he was horrified to experience segregated white and black RC mass services. Worse still, the local white kids received a decent education at small publicly-funded schools, but the black children got no formal education at all.

Fr Matt had a vision of opening the deep South’s first mixed race Catholic High School, and so he attended night classes at the local New Orleans university for 5 years graduating with yet another degree; this time a Masters in Education. During this period, Matt became an active campaigner in the burgeoning civil rights movement of the time, trying to gain equality for black Americans. Traditional white supremacists sneered at the Catholic Church’s involvement, and several senior priests were arrested on trumped-up civil disturbance charges. Looking back, Fr Matt wrote:

Fr Matt had a vision of opening the deep South’s first mixed race Catholic High School, and so he attended night classes at the local New Orleans university for 5 years graduating with yet another degree; this time a Masters in Education. During this period, Matt became an active campaigner in the burgeoning civil rights movement of the time, trying to gain equality for black Americans. Traditional white supremacists sneered at the Catholic Church’s involvement, and several senior priests were arrested on trumped-up civil disturbance charges. Looking back, Fr Matt wrote:

“Discrimination because of race was almost total. Segregation was everywhere — in the schools, in public transportation, in the stores, in banks, in restaurants, at lunch counters, in the movie theaters, in the parks and swimming pools. Worst of all, there was de facto segregation in the southern churches.”

During these mature student days, Fr Matt eventually assumed full authority over the Raymond Parish of New Orleans. At the time of becoming PP, his city center Catholic Church was still holding one Sunday mass for the white congregation, and then a separate service for the black parishioners, mainly because the influential local white politicians demanded that segregation must be upheld in all public places. Fr Matt announced one week after taking control that there would be just one combined mass service under his ministry, in future. The New Orleans white so-called Christians were up in arms. Fr Matt told them to accept the way forward, or to go and find a different religion. The whites reluctantly accepted Fr Matt’s decision, and crowded into all the pews up front, with the blacks having to stand at the back. Fr Matt wasn’t finished. During his first combined mass sermon, he asked the black senior citizens to walk up the aisle, and he instructed the white families to shuffle around and find seats for their elderly fellow-parishioners. The “change” in local society had started.

In 1950, Fr Matt presided over the building of a new Josephite catholic parish high school. He was appointed the first-ever principal of St Augustine’s in 1951, and served in this role for a decade. Fr Matt invited the “excluded” local black children to attend his school, again to the alarm of much wealthier white families. Even the uneducated black kids were disinclined to join academic classes, so Matt recruited top sports coaches and encouraged the reluctant scholars to venture through the school gates and form initially all-black sports teams. A major turning point came when Matt arranged end-of-term challenge matches in football and basketball, whites v blacks. The whites scoffed but were forced to eat their words when the “Negro teams” trounced their new schoolmates at everything, including track and field events.

Soon after, Matt organized sports tournaments with neighboring schools. Most were unwilling to permit games with St Augustine’s mixed race athletes, but St Augustine’s teams invariably won the scaled-down competitions – and so each exclusive whites-only school lined up to attempt to beat the New Orleans champions from St Augustine’s; a mixed bunch of intelligent liberal white boys and promising muscular black athletes. Integration had been commenced forever, unwittingly in the eyes of white bigots. Of course, Fr Matt was soon able to tell his black sports stars that they had to join the academic classes if they wanted to remain on the sports teams.

Matthew’s foresight and determination was soon recognized by his superiors. He  eventually rose through the ranks of Josephite society, and became Director of Education during the turbulent 1960’s decade. Fr Matt now had the power and ability to mould the curriculums and entrance policies of every Christian school or college across America. Today, many black Louisiana politicians, business leaders and sports celebrities pay homage to Fr Matt (fondly nicknamed “The Chief”) and their all-round education at St Augustine’s during the 1950’s and in subsequent years. In truth, most African American students in the USA, past and present, should thank my Irish American first cousin for his relentless courage in gaining equal access to educational institutions for all races – something which is now taken for granted.

eventually rose through the ranks of Josephite society, and became Director of Education during the turbulent 1960’s decade. Fr Matt now had the power and ability to mould the curriculums and entrance policies of every Christian school or college across America. Today, many black Louisiana politicians, business leaders and sports celebrities pay homage to Fr Matt (fondly nicknamed “The Chief”) and their all-round education at St Augustine’s during the 1950’s and in subsequent years. In truth, most African American students in the USA, past and present, should thank my Irish American first cousin for his relentless courage in gaining equal access to educational institutions for all races – something which is now taken for granted.

Fr Matt visited his mother’s Irish hometown of Tubbercurry on several occasions, and composed his own hand-written version of a Family Tree after seeking out and interviewing relatives. About 10 years ago, I was privileged to be personally introduced to Fr Matt by a new-found NYC-based cousin, as Matt served in his last SSJ role as the Rector of St Joseph Manor in Baltimore, a retirement home for ailing priests from the 1990’s onward. He graciously sent me his detailed O’Rourke Family Tree, and I was therefore able to vastly expand my Neary Family Tree. I reciprocated his kindness by retrieving several Irish vital records featuring his father and uncles, and their forefathers, which Matt had never been able to locate. He said that I had made him a “very happy and contented old man” as he prepared to meet his Maker.

Fr Matt visited his mother’s Irish hometown of Tubbercurry on several occasions, and composed his own hand-written version of a Family Tree after seeking out and interviewing relatives. About 10 years ago, I was privileged to be personally introduced to Fr Matt by a new-found NYC-based cousin, as Matt served in his last SSJ role as the Rector of St Joseph Manor in Baltimore, a retirement home for ailing priests from the 1990’s onward. He graciously sent me his detailed O’Rourke Family Tree, and I was therefore able to vastly expand my Neary Family Tree. I reciprocated his kindness by retrieving several Irish vital records featuring his father and uncles, and their forefathers, which Matt had never been able to locate. He said that I had made him a “very happy and contented old man” as he prepared to meet his Maker.

Shortly after his sister Margaret Mary died in Nov 2008, Matt took a heavy fall and broke his hip in seven places and fractured his femur. He was now aged 90 and even his nursing staff felt that the much-loved Fr Matthew would never recover from this devastating accident – but he did. Eventually confined to a wheelchair, Matt was able to communicate with me in Ireland via the phone and with his regular letters and blessings. Remarkably, Fr Matt had become fully computer-literate in old age, and he even sent me the odd e-mail as a disabled nonagenarian to advise me of the births of new family tree members across the world.

The renowned published author, civil rights pioneer and former School Principal and President, with the film star good looks, the Very Reverend Father Matthew Joseph O’Rourke, SSJ, passed away peacefully on 9th March 2012 at St Joseph Manor. He was buried on 14th November at the New Cathedral Cemetery in Baltimore.

Irish Nature

One of the joys of living and working in the rural West of Ireland countryside is that you become well-acquainted with all species of domesticated and wild creatures which you rarely get to see in the towns and cities – and I’m not talking about the human varieties, such as Hughie & Maurice!

Gazing out of my office window on my half-acre plot, depending on the time of year, I view in close-up all manner of things from the animal and bird kingdoms. There’s hares and rabbits peeping out from the edge of the woods opposite, and often a beautiful fox stealthily creeping across the meadow in search of his long-eared prey. Thankfully, we never see the “kill” as foxes drag their quarry to undergrowth for the final execution.

In the next field, there are two donkeys which roll on their backs in play when the sun shines. Maybe they are discouraging pesky insects from crawling inside their thick coats. Donkeys must always have company to thrive – so never rear a donkey in isolation.

Cattle and sheep are rotated on the meadow. The sheep are the loudest, especially just after lambing when the ewes call out for their twins or triplets. Each ewe has a distinctive voice, and the lambs instantly recognize the call of their mother and frolic back to her side, leaping and high-kicking their young limbs, when they’ve wandered too far away. Some ewes sound scarily masculine with deep booming voices. Many is the day that I’ve turned toward the meadow believing that one of my male farming neighbours is calling for my attention. The cattle get louder in winter when brought indoors to their sheds. If one old girl calls out for her daily silage feed, then she sets off a chain reaction of incessant “loo-ing” until the herdsman dishes out the grass. Cows in Connaught “loo” not “moo” – it’s a subtle difference.

It’s always a treat to see the hedgehog or badger ambling along at dusk by the river. At the other end of the spectrum, everyone rushes to chase off the non-native [American] mink, if spotted. These fine looking animals were introduced into Ireland and farmed for their fur. Unfortunately, many have escaped their compounds and now they breed freely in the countryside. The problem is that these creatures are “killing machines” pure and simple. They will attack and destroy any other small animal on their patch, whether it be cats, dogs, hens or other wildlife. Minks kill to dominate territory, whereas a fox will only kill for food.

Bird-life is abundant in our garden. We put out feeders and seed to encourage our feathered friends, all year round. There are the noisy black crows who feed at dawn, and squabble among themselves. If we fatten the crows up here, then the local grain and vegetable growers stand a better chance of maintaining a healthy crop, we believe. Next in at breakfast time are the gentle wood pigeons. I call them Love Birds. They always go around in twos, one male and one female, and reputedly keep the same partner for life. Aw!

The little fellas arrive soon after. The big wild pigeons happily share their meal with the sparrows and finches and tits and thrushes. Now and again the robin shows his face and chest. Always a loner, not like the loved-up pigeons. The timid wrens from the riverbank sometimes swoop in as well if the weather determines that worm and insect-hunting is leaving them a bit famished. We have been particularly pleased this year to see that the once-rare goldfinch is thriving around our garden. In fact, just of late, this pretty yellow-feathered species might be outnumbering all the rest. It is hard to count numbers accurately when you reach 30+ for one breed and all the recently hatched goldfinch chicks won’t keep still, busily cracking open the Niger Seeds.

Of course, my favourite birds refuses to partake in the freebie meals on offer. These are the fiercely independent and abundant swallows – after returning in the spring or early summer from their winter vacation, thousands of miles away in sunny Africa. With their own in-built SatNavs, somehow year after year the same pairs return at gradual intervals to our relatively tiny garden, or more precisely the roof eaves and outbuildings. Before long, a dozen or so spruced up mud nests appear, and mating begins during dazzling aeronautical displays. Then you notice that the ladies retire to the nests for a while, and leave the man of the house to get the groceries. In no time at all, chirping is heard above the window tops or in the barn roof, and soon after three or four tiny faces peep out from their dried mud homes.

It is the biggest delight of all to watch the baby swallows grow, day by day, until the very hour that mother has to be cruel to be kind. This is the time when she watches from afar but refuses to feed her chicks ever again. The youngsters must now fend for themselves – and this means attempting that strange exercise of flying at which their parents are so adept. Some chicks need more encouragement than others. Dad often soars and swoops doing his loop-the-loops right outside the nesting zone. The kids get the message. They must make a leap of faith and test out their wings. I was privileged last year to witness the very moment when one young swallow made his maiden flight. He leapt from the nest rim, and fell towards the ground flapping for all his worth. Miraculously, he never hit the deck because in an instant of wonderment, the tiny bird hovered a few inches off my concrete path. And then, the knack of flying was discovered. He started to rise, slowly; just enough to clear the roof of my car – until dad swooped by and said “Follow me.” The offspring did as he was told, and commenced his first horizontal journey, soon followed by a climb, a sharp turn, a dive and a well-deserved short breather on a branch of the willow tree by the river.

His two siblings soon joined him, making almost identical take-offs as they jumped like virgin parachutists from their former home in the eaves.

Ned’s Field

Apart from my grandfather Ned being (in)famous for funding Ireland’s longest ever pub crawl, I have only managed to pick up one or two other snippets of information about his life in south Sligo prior to his lifelong relocation to the windy moors of east Lancashire.

I am proud to say that one particular field in all of Sligo is still referred to as Ned’s Field. It’s a grand field, leading uphill to an ancient ring fort. It was sold to good neighbours called O’Hara in the 1930’s in order to finance the family’s “emigration” to the Promised Land of booming Lancs (just before WW2 broke out). I like to walk up Ned’s Field. It’s a pity that Ned’s cottage is no more – but Uncle John Neary’s place, right next-door still remains, and was occupied by John until very recently.

Prior to the departure of my Neary ancestors, a few memories remain, recalled by folk old enough to remember. For instance, old “uncle” John James Neary (2nd or 3rd cousin) born in 1924 laughs when he tells me how Ned saved on the regular cottage heating fuel of turf sods cut from the local bog (and dried and turned for weeks on end). Uncle John can recall going into Ned’s cottage and witnessing him burning a fallen tree trunk which was so lengthy that one end was on the fire whilst the slimmer end was poking out of the cottage door and into the “street” (as John describes a single track lane used by just two inter-related farming families). This tree trunk would burn away for a week or so, and would be shunted up to the fire by a few inches when necessary. Talk about domestic health & safety! These cottages had thatched roofs made of dried straw or rushes. Very flammable substances. A spark could have set the whole place alight – but it never seemed to happen. The Neary family would sleep through the night with their own form of central heating. The fires in south Sligo never went out, 24/7.

John also told me that “Kit” (Kate) Stenson, aka grandma [1852-1944], was always in her bed in the “top room” when he was brave enough to venture into Ned’s shack. The “top room” was the only separate bedroom in a traditional Irish cottage. The other 10 or 12 or 14 younger occupants (plus sow) lived in the same cramped space, maybe separated by thin cloth sheets hung from the rafters at bedtime. John told me that Kit was very kind to the young kids. She would put down her clay pipe and reach under her bedclothes and produce the equivalent of sweets or toffees for the modern child. John loved his childhood treats.

My dad’s best school friend pal in the 1930’s was Eddie or Ned Moran. This man is still living, but sadly he is now inflicted with total blindness. His memories are vivid. He tells me of rushing home from school with my dad (both bare-footed) with the intention of riding Ned Neary’s donkeys bareback, up on Ned’s Field. Worryingly he says that “Ned’s asses” were so thin that they would “split you in two”.

Ned Moran was also there when my Neary clan pulled out of the “street” and never returned. Apparently my dad shouted from the cart that he would see Eddie next summer. The two school friends never saw each other again. Unbeknownst to them, a simmering Neary feud about a trespassing sow or a wandering cock determined that Ned Neary’s family would never again set foot on their home sod [until I instigated a truce 70 years later]. Details to follow.

Eddie Moran said that he was brave as he waved my father off to England. He kept smiling and laughing, as instructed. His mother (Annie Gilmartin) had told him to be strong. Then Eddie brought a tear to my eye as he explained that he cried all the way home across the field, after Ned Neary’s ox-cart had departed for the railway station. His best mate, John Thomas Neary, never saw or contacted Eddie Moran again – but Eddie remembers him with fondness, and chuckles away at his memories of Ned’s Field, eighty years ago..

My Grandad’s (In)Famous!

When you research your family history, you secretly hope that you will uncover a tale or two which makes your ancestry unique, and possibly famous. You know, the type of story you can impress your friends with over dinner or whilst sharing a pint. By interviewing old folks who remembered my Irish grandfather’s existence in Sligo, before his permanent relocation to England, I was able to verify one such story. More than one person recalled the same tale – so this saga was “famous” considering that the events happened over 80 years ago!

At the time, my grandad Ned Neary was approaching 30 years of age, married with a clutch of young kids, with my dad being the eldest born in 1925. It was the day of the Old Fair Day in Tubbercurry renowned for fast and furious livestock sales, all conducted on the narrow streets and pavements of the town. Ned knew that the Old Fair would attract some cash-laden jobbers down from the North. These were cattle-dealers contracted to buy up the best stock in the Republic and cart them back to wealthy farmers in Ulster where beef prices were sky-high. As a result, Ned spent the eve of the Fair Day sprucing up his two finest calves. Their coats were washed and brushed until they were gleaming.

Early next morning, as planned, Ned’s best friend Tailor Currane from Gurtermone, ambled down the lane to the tiny Neary farmstead to assist with the transportation of the two prized calves. This involved attaching a leash to each young animal and then walking them all the way into town, ensuring that they remained in pristine condition. The plan went like clockwork, and Ned secured a prime bartering position at the bottom end of The (triangular) Square in Tubbercurry, just as the jobbers rolled into town. No-one quite knows what happened next, but clearly more than one jobber took an instant interest in Ned’s calves, and the outcome was a bidding war which resulted in Ned reputedly receiving a handshake of honourable spit – and the highest sum ever paid at the time for a pair of wee calves. Something in the region of £20 or more; a fortune circa 1930.

Well now, Tailor Currane was not stupid, although he was not a good tailor, and consequentially virtually penniless. He knew that his wages for the day would be paid in the form of a slap-up breakfast and a few drinks from the proceeds of the sale. He also knew that Ned was a fierce drinker, as witnessed when Ned’s notorious home-brewed Mad Man’s Soup was often devoured before it had cooled from the Still. So right enough, Ned and Tailor Currane went for a celebration drink right there in the town square. Flush with pound notes they had large measures – and to Hell with breakfast.

By late morning, Neary and Currane decided to embark on a pub crawl, to get farther away from the noisy farmers and jobbers who were now all arguing about the ridiculous price standard set by Ned’s early sale. All had to settle for less, except Neary and Currane who drank their way to the edge of town by mid-afternoon.

Their bahaviour was becoming more raucous, and not welcomed in the more respectable Tubber hotels, so Ned bought a drink for a farming friend from Curry on the agreement that he would ferry Ned & Tailor to their local hostelry at Kilcoyne’s in the back of the farmer’s ox cart. When passing Rhue, Ned decided that it was too early to be heading homeward, so he told his taxi driver to take the passengers all the way into Curry village. “We’ll have one or two in Cawley’s bar,” shouted Ned, to Currane’s delight.

Well, one or two became three or four more, and our intoxicated duo rambled from public house to coaching inn to hotel. When no longer tolerated in Curry, Ned and his buddy staggered down the main road south towards Charlestown. They’d worked up a big thirst by the time they reached the first bar in Bellaghy – so they had a drink. Onward they trekked. Ned was in Mayo by midnight, in the bright lights of Charlestown. He was now farther away from his wife and family than he had been at breakfast time, but he was in no fit state to go home. Anyway, Ned had hardly made a dent in the proceeds from his cattle sale – so he negotiated the purchase of a few after-hours drinks at Top Dollar provided that he and his comatose friend were granted lodgings for the night. The innkeeper obliged and showed Neary & Currane into a chic barn in the back-yard which had a welcoming hay-loft above. The intrepid duo drank themselves to sleep in the penthouse suite.