If any of your ancestors were raised as Catholics, consider looking for a record of their Confirmation. This holy event is one of the seven sacraments in which Catholics participate as they pass through life. According to Catholic doctrine, in this sacrament participants are sealed with the gift of the Holy Spirit and are strengthened in their Christian life.

Traditionally, these days, Confirmation is the third of the three sacraments of Christian initiation (following Baptism and First Holy Communion) normally undertaken when Catholic children are in their early teens. However, in ancient times and still today in some more obscure parts of the world, a younger Catholic child could be “confirmed” prior to Holy Communion, so long as the baptism ceremony had been completed.

Fortunately, history dictates that the vast majority of our Irish ancestors were raised as Catholics, so if you have Irish heritage, then extend your vital record search criteria for each Irishman or woman to the following events. A written record of each occasion would have been registered at the time.

Fortunately, history dictates that the vast majority of our Irish ancestors were raised as Catholics, so if you have Irish heritage, then extend your vital record search criteria for each Irishman or woman to the following events. A written record of each occasion would have been registered at the time.

- Birth / Baptism

- Confirmation

- Marriage (if applicable)

- Death

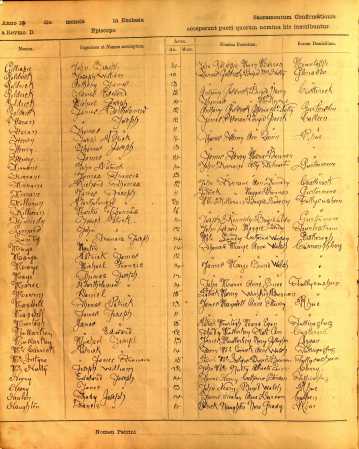

Recently, I was delighted to find a preserved copy of my Irish grandfather Ned’s Confirmation record held in the custody of his native RC parish church in Tourlestrane, County Sligo. The library in the Parochial House had the usual Baptismal and Marriage Registers but I noticed a smaller section headed Liber Confirmatarum or Confirmation Book. This hand-written register had only been formally kept since the start of the 20th century but this was late enough to include the Confirmation of the 12th and last child of Tom Neary & Kate Stenson born in May 1894. In fact, Ned Neary must have been one of the oldest participants (at age 15) to receive the Bishop’s blessing because the date of the event was May 1909. The poor education of Ned and his parents was displayed by the fact that my grandfather was wrongly registered as a fourteen year-old.

Confirmation records are very interesting because they record the full names (and “reported” ages) of all the ancestral children in a generation who lived into their teens. This information may not appear in registered format anywhere else. It is easy to detect siblings where the full names and address of each child’s parents were recorded, as shown here. In some instances, the parental data might enlighten or verify your understanding of a mother’s maiden surname which was not forthcoming from other research sources.

This information may not appear in registered format anywhere else. It is easy to detect siblings where the full names and address of each child’s parents were recorded, as shown here. In some instances, the parental data might enlighten or verify your understanding of a mother’s maiden surname which was not forthcoming from other research sources.

As part of the Confirmation ceremony, each child is awarded a Confirmation forename which must be an established Catholic saint’s name. My grandfather chose a popular one, Joseph, but the record above is the only document I possess which proves that Edward Neary ever had a middle name. So, 120 years after his birth, my granddad can now be officially referred to as Edward Joseph Neary.

Perhaps even more poignant for me was reading the Confirmation record of my granddad’s sister, and the 11th child of Tom & Kate. This was the Neary girl known by the giggle-inducing name of Fanny who no-one could seem to recall. My earlier detective work verified that she was born in April 1892, but she passed away at the age of just 25 in the Sligo Asylum Hospital. Now, at last, funny Fanny had a proper and saintly title. As a young teenager in St Attracta’s RC church, my “lost” great-aunt was blessed with the full name of Fanny Mary Agnes Neary.

I am so glad that she chose a female saint’s name. 100 years ago, the vogue at Confirmation time in Ireland seems to have been that boys picked boys’ names, but girls could choose either gender. The Confirmation Book shows many examples of poor ill-advised teen-aged girls choosing new but odd male middle names such as Aloysius or Stanislaus.

One last research tip, worth remembering. Our Irish ancestors had a strange tendency of adopting their middle names as alternative new first names in adulthood, particularly if they migrated abroad. When searching for those elusive records featuring your forefathers (and mothers!), don’t forget that extra Confirmation Name as you fill in the search data box.

Then again, I can’t imagine that “Stanislaus Brennan, gender: female” will return many search results … unless she became a nun … but that’s another story for another day.