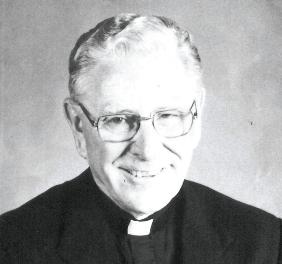

I have previously referred to a Black Sheep in the family, in the form of an abusive priest of the worst kind. I am pleased to be able to introduce the antithesis of the abuser, the holiest man in my Family Tree, none other than Father Matthew O’Rourke, my first cousin once removed.

Matthew was born on 7th November 1918 in the Bronx district of New York City. He was the middle child of five O’Rourke siblings born to one of my grandfather Ned Neary’s sisters (Margaret) who had emigrated from the Sligo farmstead to New York in 1905. In the Bronx, Margaret married her brother-in-law, John O’Rourke, a Leitrim native and a fully-qualified and respected Civil Engineer who worked on many important NY infrastructure projects.

Margaret Neary’s first child, a daughter called Mary, died before the age of two when Margaret was six months pregnant with her second child. The new baby would have started to console John & Maggie O’Rourke over their sad loss, as this child was also a daughter, honourably christened as Margaret Mary in September 1916. The new baby developed into a strong, bright and independent young lady. By 1938, Margaret Mary had breezed through college studies and went in search of a career having been awarded a Major in the field of Chemistry. In 1940, Margaret Mary would have witnessed her younger brother Matthew leaving college with his own BA degree and then attending St Joseph’s Seminary to study to enter the priesthood. Matthew’s life choices must have influenced his older sister because in 1949 Margaret Mary gave up her well-paid employment and became a nun in the Order of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament. In fact, Margaret Mary lived her own long and holy life as she too devoted herself to God, becoming a Catholic teacher of native Najavo Indians in Arizona before eventually retiring to her convent in Pennsylvania. Margaret Mary died on 7th November 2008 in the convent hospital, aged 92, an event which upset Fr Matthew … for he was still going strong, and it was his birthday and he related the news of Margaret Mary’s death to me with much sadness in his voice.

During his seminary studies, Matthew was sent in 1944 to work in the poorest black communities of the Southern US states. He spent about a year in these communities, and what he saw was to inspire the majority of his adult life. Matt was fully ordained as a Josephite priest on 10th June 1947 after completing his ecumenical studies in Washington DC. He was awarded his first ministry as an associate pastor in a mixed race city center parish of New Orleans, and here he was horrified to experience segregated white and black RC mass services. Worse still, the local white kids received a decent education at small publicly-funded schools, but the black children got no formal education at all.

Fr Matt had a vision of opening the deep South’s first mixed race Catholic High School, and so he attended night classes at the local New Orleans university for 5 years graduating with yet another degree; this time a Masters in Education. During this period, Matt became an active campaigner in the burgeoning civil rights movement of the time, trying to gain equality for black Americans. Traditional white supremacists sneered at the Catholic Church’s involvement, and several senior priests were arrested on trumped-up civil disturbance charges. Looking back, Fr Matt wrote:

Fr Matt had a vision of opening the deep South’s first mixed race Catholic High School, and so he attended night classes at the local New Orleans university for 5 years graduating with yet another degree; this time a Masters in Education. During this period, Matt became an active campaigner in the burgeoning civil rights movement of the time, trying to gain equality for black Americans. Traditional white supremacists sneered at the Catholic Church’s involvement, and several senior priests were arrested on trumped-up civil disturbance charges. Looking back, Fr Matt wrote:

“Discrimination because of race was almost total. Segregation was everywhere — in the schools, in public transportation, in the stores, in banks, in restaurants, at lunch counters, in the movie theaters, in the parks and swimming pools. Worst of all, there was de facto segregation in the southern churches.”

During these mature student days, Fr Matt eventually assumed full authority over the Raymond Parish of New Orleans. At the time of becoming PP, his city center Catholic Church was still holding one Sunday mass for the white congregation, and then a separate service for the black parishioners, mainly because the influential local white politicians demanded that segregation must be upheld in all public places. Fr Matt announced one week after taking control that there would be just one combined mass service under his ministry, in future. The New Orleans white so-called Christians were up in arms. Fr Matt told them to accept the way forward, or to go and find a different religion. The whites reluctantly accepted Fr Matt’s decision, and crowded into all the pews up front, with the blacks having to stand at the back. Fr Matt wasn’t finished. During his first combined mass sermon, he asked the black senior citizens to walk up the aisle, and he instructed the white families to shuffle around and find seats for their elderly fellow-parishioners. The “change” in local society had started.

In 1950, Fr Matt presided over the building of a new Josephite catholic parish high school. He was appointed the first-ever principal of St Augustine’s in 1951, and served in this role for a decade. Fr Matt invited the “excluded” local black children to attend his school, again to the alarm of much wealthier white families. Even the uneducated black kids were disinclined to join academic classes, so Matt recruited top sports coaches and encouraged the reluctant scholars to venture through the school gates and form initially all-black sports teams. A major turning point came when Matt arranged end-of-term challenge matches in football and basketball, whites v blacks. The whites scoffed but were forced to eat their words when the “Negro teams” trounced their new schoolmates at everything, including track and field events.

Soon after, Matt organized sports tournaments with neighboring schools. Most were unwilling to permit games with St Augustine’s mixed race athletes, but St Augustine’s teams invariably won the scaled-down competitions – and so each exclusive whites-only school lined up to attempt to beat the New Orleans champions from St Augustine’s; a mixed bunch of intelligent liberal white boys and promising muscular black athletes. Integration had been commenced forever, unwittingly in the eyes of white bigots. Of course, Fr Matt was soon able to tell his black sports stars that they had to join the academic classes if they wanted to remain on the sports teams.

Matthew’s foresight and determination was soon recognized by his superiors. He  eventually rose through the ranks of Josephite society, and became Director of Education during the turbulent 1960’s decade. Fr Matt now had the power and ability to mould the curriculums and entrance policies of every Christian school or college across America. Today, many black Louisiana politicians, business leaders and sports celebrities pay homage to Fr Matt (fondly nicknamed “The Chief”) and their all-round education at St Augustine’s during the 1950’s and in subsequent years. In truth, most African American students in the USA, past and present, should thank my Irish American first cousin for his relentless courage in gaining equal access to educational institutions for all races – something which is now taken for granted.

eventually rose through the ranks of Josephite society, and became Director of Education during the turbulent 1960’s decade. Fr Matt now had the power and ability to mould the curriculums and entrance policies of every Christian school or college across America. Today, many black Louisiana politicians, business leaders and sports celebrities pay homage to Fr Matt (fondly nicknamed “The Chief”) and their all-round education at St Augustine’s during the 1950’s and in subsequent years. In truth, most African American students in the USA, past and present, should thank my Irish American first cousin for his relentless courage in gaining equal access to educational institutions for all races – something which is now taken for granted.

Fr Matt visited his mother’s Irish hometown of Tubbercurry on several occasions, and composed his own hand-written version of a Family Tree after seeking out and interviewing relatives. About 10 years ago, I was privileged to be personally introduced to Fr Matt by a new-found NYC-based cousin, as Matt served in his last SSJ role as the Rector of St Joseph Manor in Baltimore, a retirement home for ailing priests from the 1990’s onward. He graciously sent me his detailed O’Rourke Family Tree, and I was therefore able to vastly expand my Neary Family Tree. I reciprocated his kindness by retrieving several Irish vital records featuring his father and uncles, and their forefathers, which Matt had never been able to locate. He said that I had made him a “very happy and contented old man” as he prepared to meet his Maker.

Fr Matt visited his mother’s Irish hometown of Tubbercurry on several occasions, and composed his own hand-written version of a Family Tree after seeking out and interviewing relatives. About 10 years ago, I was privileged to be personally introduced to Fr Matt by a new-found NYC-based cousin, as Matt served in his last SSJ role as the Rector of St Joseph Manor in Baltimore, a retirement home for ailing priests from the 1990’s onward. He graciously sent me his detailed O’Rourke Family Tree, and I was therefore able to vastly expand my Neary Family Tree. I reciprocated his kindness by retrieving several Irish vital records featuring his father and uncles, and their forefathers, which Matt had never been able to locate. He said that I had made him a “very happy and contented old man” as he prepared to meet his Maker.

Shortly after his sister Margaret Mary died in Nov 2008, Matt took a heavy fall and broke his hip in seven places and fractured his femur. He was now aged 90 and even his nursing staff felt that the much-loved Fr Matthew would never recover from this devastating accident – but he did. Eventually confined to a wheelchair, Matt was able to communicate with me in Ireland via the phone and with his regular letters and blessings. Remarkably, Fr Matt had become fully computer-literate in old age, and he even sent me the odd e-mail as a disabled nonagenarian to advise me of the births of new family tree members across the world.

The renowned published author, civil rights pioneer and former School Principal and President, with the film star good looks, the Very Reverend Father Matthew Joseph O’Rourke, SSJ, passed away peacefully on 9th March 2012 at St Joseph Manor. He was buried on 14th November at the New Cathedral Cemetery in Baltimore.